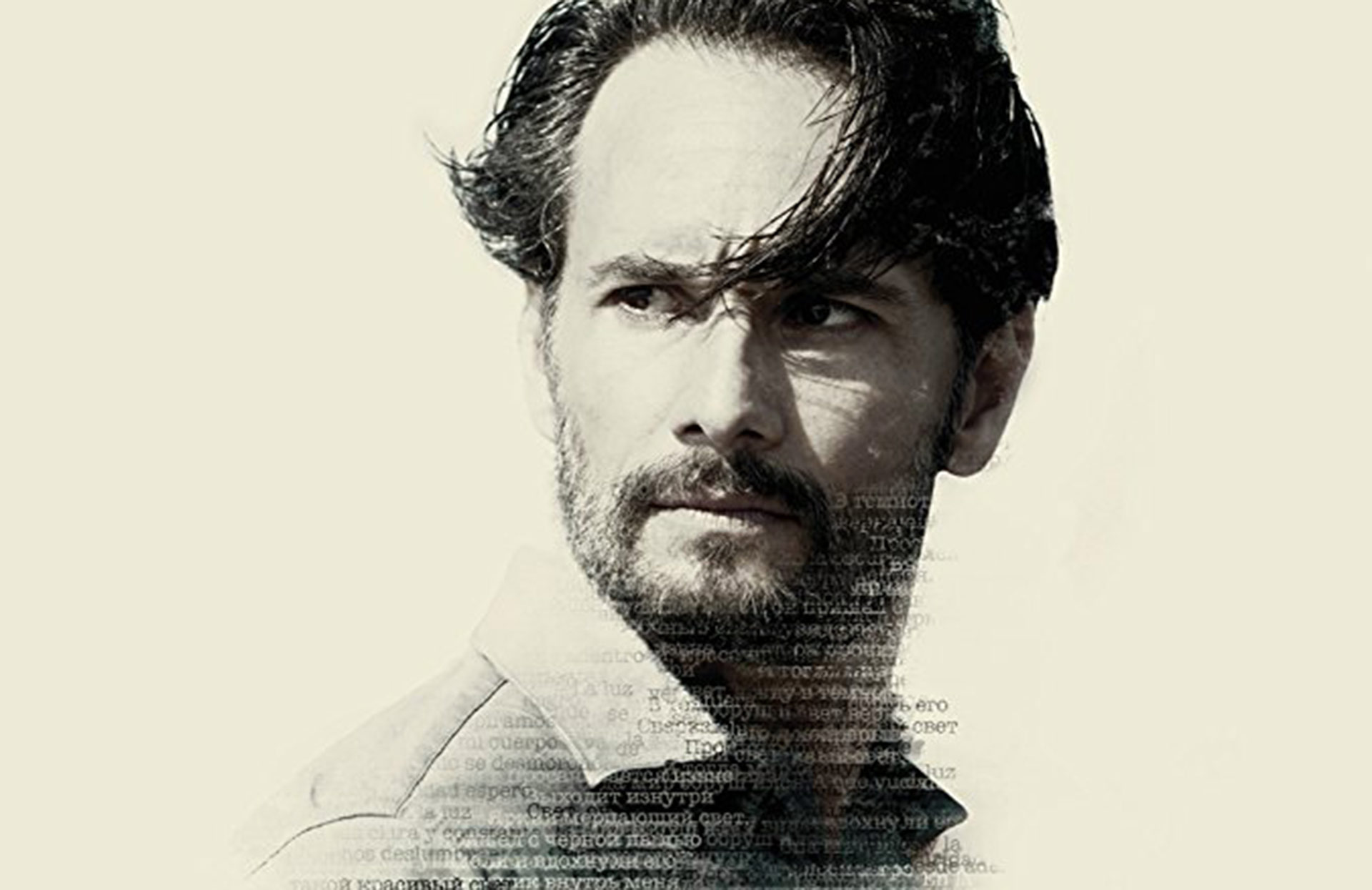

'Westworld' star Rodrigo Santoro plays the title character in

a story involving Cuba's medical treatment of patients from

the Chernobyl disaster.

The focus of Un Traductor is a little-known chapter in the

history of Cuba, certainly one that went unmentioned in most

obits for Fidel Castro: After the catastrophic accident at the

Soviet Union's Chernobyl nuclear plant, the Caribbean nation

opened its highly regarded medical facilities to many of the

Russian patients suffering from radiation-related diseases.

The first feature by sibling directors Rodrigo and Sebastián

Barriuso is a handsomely shot Cuban-Canadian production that

explores this life-and-death diplomacy through one man's

unlikely — and government-mandated — participation in it.

Brazilian star Rodrigo Santoro (Westworld, The 33) plays

Malin, a professor of Russian literature who's ordered out of

the classroom and into the hospital, to serve as a translator

between medical staff and patients.

The drama begins in 1989, three years after the Chernobyl explosion and in the early days of the Cuban program that would treat more than 20,000 patients over a 20-year period.

Even with significant portions of its running time centering

on desperately ill children, the film, written by Lindsay

Gossling, avoids the maudlin, its restraint mirroring the

protagonist's closely guarded emotions. It's in the late

going, before a quietly moving denouement, that the story

stumbles into the territory of pat sentiment, its expression

of admiration for Malin falling just shy of placing him on a

pedestal.

It's a lapse that can be explained, if not excused, by the

directors' personal connection to the story, revealed in end

titles: The movie's main character is based on their father,

Manuel Barriuso Andino. Flaws notwithstanding, Un Traductor is

a sensitive, eye-opening account that could travel widely.

With agile work by cinematographer Miguel Littin-Menz and

editor Michelle Szemberg, the directors segue smoothly from

news footage of Mikhail Gorbachev's Cuban visit to scenes that

place Malin and his young son, Javi (Jorge Carlos Perez

Herrera), among the Havana residents lining the streets for a

glimpse of the Soviet leader.

Soon after, Malin's home life with the boy and his artist wife, Isona (Yoandra Suárez), is disrupted by an assignment that arrives without the slightest warning or explanation. With Russian Department classes suspended, Malin and his university colleagues report, as instructed, to a hospital — one that has been turned into a facility dedicated to treating Chernobyl patients, and where the professors' language skills are crucial. After the traumatic initiation of having to tell a young mother that there's no hope for her daughter, Malin tries to get out of his night-shift duties in the children’s ward. But before long he awakens to a calling that might even be higher than that of his ivory tower. As he puts aside his thesis and lessons on Gogol to research leukemia, Malin becomes involved with all the kids on the ward, particularly a boy of about 10, Alexi (exceptionally well played by Nikita Semenov), who lies in isolation because of his compromised immune system. Both inside and outside the hospital, mothers don't come off especially well, but Malin is sympathetic to Alexi's watchful father, a high school teacher (a very good Genadijs Dolganovs, who served as a dialect coach on The Shape of Water). In one of the film's most affecting exchanges, the man recalls with bitter sorrow how honored he felt to be transferred to Pripyat, the town where Chernobyl stood, to teach the children of esteemed scientists. But it's Malin's intimate workplace bond with Argentine nurse Gladys that gives the film its heart and soul. Maricel Álvarez, who played the dissolute former wife of Javier Bardem's character in Biutiful, is superb in the part, offering an unforced blend of common sense and passion. Having escaped her native country's dictatorship, Gladys is a proud participant in Cuba's medical system, and a believer in its larger vision; she characterizes Fidel's program for Chernobyl patients as “an act of kindness by a leader with a big heart.” Such praise flows organically, unlike the moments in the final scenes when the screenplay requires her, unnecessarily, to sum up Malin's contributions; her gaze says everything that needs saying.

All of this stands in obvious contrast to Malin's healthy,

pampered son and the family's relative affluence and comfort.

As a man who's taciturn and emotionally opaque — to his wife's

growing frustration — Santoro delivers an understated

performance that conveys Malin's physical and mental

exhaustion along with his deepening engagement in his

unasked-for work.

The scenes of Malin's home life can feel stilted, but they

serve their narrative purpose, accentuating the tension

between individuality, represented by the creative force of

Isona, and the collective. And they bring home the day-to-day

effects of the breakup of the Soviet Union on Cubans, with

economic strains and shortages of goods exacerbating the

simmering conflict between Malin and Isona.

That the domestic scenes aren't as gripping as those in the

hospital is in some ways the point. Within the horror-tinged

green nighttime corridors, Malin is experiencing matters of

such urgency that anything else pales in comparison — to the

point where he dismisses Isona's work as “just art.” Tellingly

and movingly, it's only when she sees drawings by the

hospitalized children that she understands the depth of her

husband's work with them.

Shot in Havana, with vivid contributions from production

designers Zazu Myers and Juan Carlos Sánchez Lezcano, the film

captures the distinctive time-capsule quality of an isolated

country, where many aspects of the story's 1989–90 setting

bear the mark of earlier decades.

The Barriusos' film addresses a specific set of events, but as

it unfolds at the intersection of socialist ideals, economic

realities and personal ambitions, it's a timeless portrait of

what it means to be a cog in the wheel of a single-party

regime. Whether Malin's life was enriched or destroyed by his

assignment was never part of the greater equation.

Production companies: Creative Artisans Media, Involving

Pictures Cast: Rodrigo Santoro, Maricel Álvarez, Yoandra

Suárez, Nikita Semenov, Jorge Carlos Perez Herrera, Genadijs

Dolganovs, Milda Gecaite, Osvaldo Doimeadiós, Eslinda Núñez

Directors: Rodrigo Barriuso, Sebastián Barriuso Screenwriter:

Lindsay Gossling Producers: Sebastián Barriuso, Lindsay

Gossling Executive producers: Lindsay Gossling, Louis O'Murphy

Director of photography: Miguel Littin-Menz Production

designers: Zazu Myers, Juan Carlos Sánchez Lezcano Costume

designer: Samantha Chijona Editor: Michelle Szemberg Composer:

Bill Laurance Casting directors: Libia Bastia, Marsha Chesley,

Shakyra Dowling Venue: Sundance Film Festival (World Cinema

Dramatic Competition) Sales: ICM Partners

by Sheri Linden - The Hollywood Reporter